For most of us, our first introduction to maps was by a teacher at primary school. As we progressed through the education system, atlases were introduced, exposing students to the art of cartography and the science of geography. For those of us lucky enough to have an atlas in our home library we may have had an earlier exposure. With the development of the World Wide Web and smart devices, the way we consume geographic information has changed. So, have we seen the death of the Atlas?

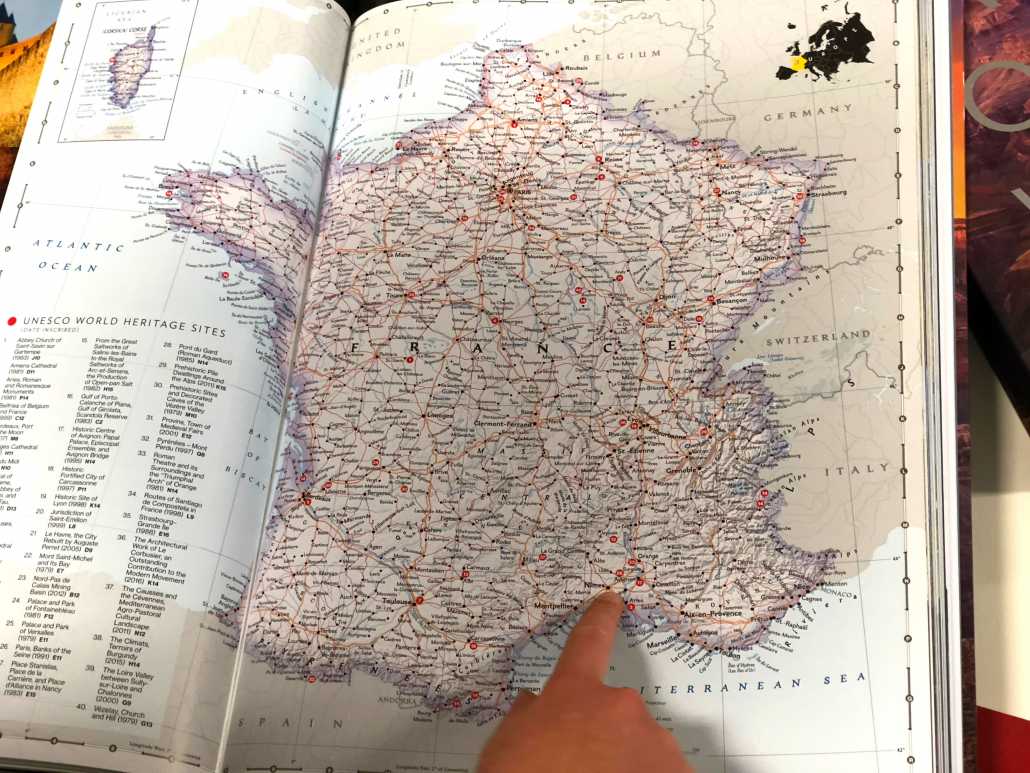

Let’s look at the reason why we use an atlas in the first place. For the younger reader, atlases are their introduction to cartographic literacy, critical thinking and the understanding of scale (Ramos, 2008). Further to these skills, an atlas also provides a comprehensive geographic resource, enabling users to search and find locations, understand geographic relationships and discover statistics and other information about countries.

There are great examples of hard copy atlases that contain beautiful cartography combined with luscious photography and beautiful data visualisations. One of the best is National Geographic’s Visual Atlas of the World, which takes a reference book to the next level. The Times Atlas is always reinventing itself, and the latest 15th edition combines the well-known detailed cartography with some additional stunning visuals. Both of these publications tick the boxes of the ‘functional requirements’ of an atlas, with the NG Visual Atlas giving an indication for the direction of atlases of the future.

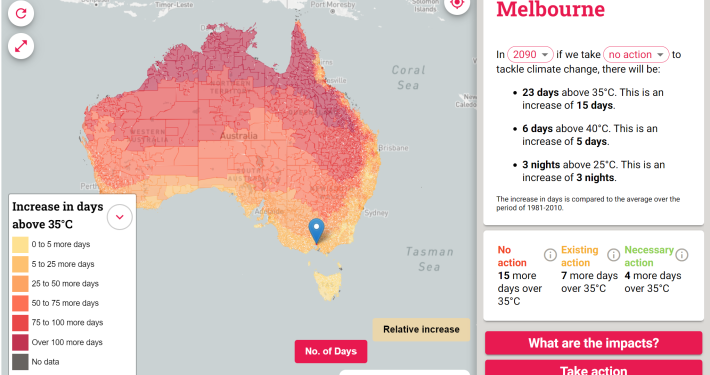

Since the introduction of the internet the concept of a multimedia, or digital, atlas has been proposed by academics and implemented in a number of exemplary cases, such as the Atlas of Switzerland, Diercke Atlas and the Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States. These digital atlases and their ilk perform the same functions of a hard copy atlas, but they have added advantages that a hard copy atlas just cannot provide.

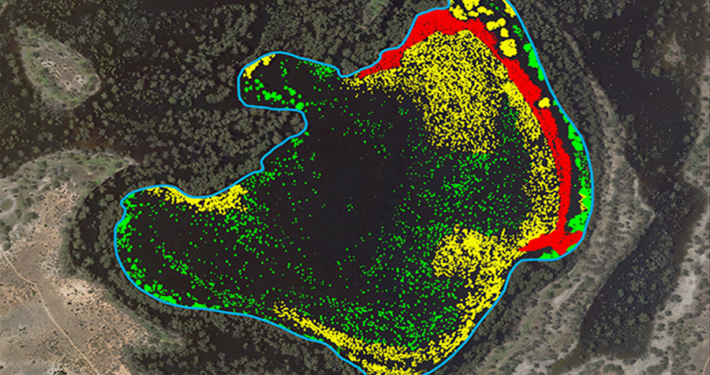

- searches and filters on data can be applied by the user to customise the output;

- maps can be presented at multiple scales allowing the user to ‘dive’ into the map to see more detail;

- data layers can be turned on and off to reveal or hide information;

- additional multimedia content, such as audio and video can be incorporated to the map provide additional context;

- near real-time layers from web services can be added to provide content that is timely and relevant; and

- three dimensional views can be incorporated, such as a globe at world scale, elevation at small scales and buildings at large scales.

In spite of all the additional content a digital atlas can provide over a hard copy atlas, there are some limitations, such as the display of the map is limited by the screen size of the viewing device. Small screen sizes don’t provide the user with context, such as, what are the locations nearby to the area I’m viewing? Navigating around a digital atlas requires menus, tools dialogue boxes and pop-ups to facilitate use and derive meaning, all of which can take up precious screen real estate. Building an atlas that can be accessible to everyone is challenging. Not all digital devices are equal—different computing power, operating systems, browsers—and not everyone has access to a computer or high-speed internet.

The most challenging problem for the digital atlas is the business model. Who will pay for access and how will they pay? We are starting to see in the educational market that the subscription based model for student atlases can work, see Jacaranda’s myworld atlas or Oxford’s digital platform or Pearson’s digital learning platform. Other than one-off grants to support the production and delivery of a nationwide digital atlas, there still hasn’t been a satisfactory business model developed for a digital atlas, the likes of NG Visual Atlas or The Times Atlas, that can present this type of engaging information.

So which delivery method is best?

My bookcase is filled with contemporary and historical atlases. There is something pleasing about the tactile nature of a book and the carefully designed cartography of an atlas. When done well, you can pour over it for hours. A digital atlas, on the other hand, can have satisfying and revealing tricks, allowing you to curate your own learning and discovery.

The cartography can also be pleasing, but there is a data-driven approach to cartography that lacks the artistic quality that the hard copy product provides.

There are fewer and fewer hard copy atlas publishers on the market now, mainly because they are a very expensive product to produce. Digital atlases are also expensive to produce, but they do have the capacity to bring more ‘bang for your buck’, if the cost model is right. Certainly updating and maintaining a digital atlas is less costly than a hardcopy atlas.

I don’t think we’ve seen the death of the atlas just yet, however it is more challenging for hard copy publishers to make an economic argument for their publication. Likewise, the cost model for a digital atlas has yet to be bedded down. As long as we have free maps on our smart devices and computers, users will defer to these products rather than a reference source to search for locations or determine a route.

For further information, please contact Spatial Vision at info@spatialvision.com.au

- Case Study: GIS Service Plan - July 24, 2024

- Climate Change Statement - November 9, 2021

- Welcome Ryanne Firme – Digital Cadastre Modernisation Team - May 21, 2021