Using Spatial Vision’s Pacific Geospatial Skills Development Program, we set out to find evidence to support the case for enhancing geospatial maturity within Fiji.

Research was carried out by our inaugural Pacific Program candidate, Lani Rokotuiwakaya, who gained insight into the needs, drivers and challenges relating to geospatial services across various levels of government – resulting in a discussion paper and recommendations.

Spatial Vision Principal Consultant (International), Kimberley Worthy

Research Methodology

Our research was led by our 2023 Pacific Program candidate, Lani Rokotuiwakaya, who conducted surveys and interviews across fifteen organisations in Fiji.

Lani aimed to establish how the current state of geospatial activity was impacting Fiji’s development and whether maturing geospatial capability, had the ability to positively influence organisational outcomes.

This work takes into account Fiji’s five-year country-level action plan endorsed by the United Nations Committee of Experts on Global Information Management (UN-GGIM). It developed the Pacific Geospatial and Surveying Council, which aims to strengthen geospatial capability across the region. This work compiles evidence to support a set of recommendations for decision-makers to consider implementing at an organisational level.

Key insights

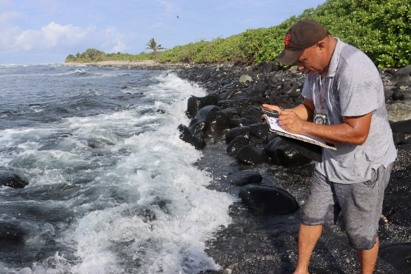

Geospatial technology is being used across critical areas in Fiji including agriculture, fishing, land administration, health services, disaster response, climate adaptation, biosecurity and environment.

The research revealed there are development needs in the following areas:

- Capability and capacity

High staff turnover, limited skill sets and lack of succession planning, prohibits the development of Fiji’s own resources to support future needs and access to technology is limited. - Data quality, access and dissemination

Multiple datastores, minimal visibility over data availability and inconsistent quality measures result in duplication of effort and low trust in data. Missing datasets and metadata prohibit operational delivery. - Geospatial governance

Geospatial leaders need developing so that requirements can be escalated to senior levels and supported through articulation of roles, responsibilities, processes and policies. - Inclusion of geospatial in organisational strategies and budget cycles

Low prioritisation of geospatial investment makes it difficult for geospatial initiatives to gain support and traction. The perceived high software costs are prohibitive for many.

Recommendations

At an organisational level, changes can be made that will enhance geospatial maturity and develop Fiji’s overall capability.